Kubernetes Solutions

22 May 2019Managing Deployments Using Kubernetes Engine

Introduction to deployments

Heterogeneous deployments typically involve connecting two or more distinct infrastructure environments or regions to address a specific technical or operational need. Heterogeneous deployments are called “hybrid”, “multi-cloud”, or “public-private”, depending upon the specifics of the deployment. For the purposes of this lab, heterogeneous deployments include those that span regions within a single cloud environment, multiple public cloud environments (multi-cloud), or a combination of on-premises and public cloud environments (hybrid or public-private).

Various business and technical challenges can arise in deployments that are limited to a single environment or region:

- Maxed out resources: In any single environment, particularly in on-premises environments, you might not have the compute, networking, and storage resources to meet your production needs.

- Limited geographic reach: Deployments in a single environment require people who are geographically distant from one another to access one deployment. Their traffic might travel around the world to a central location.

- Limited availability: Web-scale traffic patterns challenge applications to remain fault-tolerant and resilient.

- Vendor lock-in: Vendor-level platform and infrastructure abstractions can prevent you from porting applications.

- Inflexible resources: Your resources might be limited to a particular set of compute, storage, or networking offerings.

Heterogeneous deployments can help address these challenges, but they must be architected using programmatic and deterministic processes and procedures. One-off or ad-hoc deployment procedures can cause deployments or processes to be brittle and intolerant of failures. Ad-hoc processes can lose data or drop traffic. Good deployment processes must be repeatable and use proven approaches for managing provisioning, configuration, and maintenance.

Three common scenarios for heterogeneous deployment are multi-cloud deployments, fronting on-premises data, and continuous integration/continuous delivery (CI/CD) processes.

The following exercises practice some common use cases for heterogeneous deployments, along with well-architected approaches using Kubernetes and other infrastructure resources to accomplish them.

gcloud is the command-line tool for Google Cloud Platform. It comes pre-installed on Cloud Shell and supports tab-completion.

You can list the active account name with this command:

gcloud auth list

Output:

Credentialed accounts:

- <myaccount>@<mydomain>.com (active)

Example output:

Credentialed accounts:

- google1623327_student@qwiklabs.net

You can list the project ID with this command:

gcloud config list project

Output:

[core]

project = <project_ID>

Example output:

[core]

project = qwiklabs-gcp-44776a13dea667a6

Set zone

Set your working GCP zone by running the following command, substituting the local zone as us-central1-a:

gcloud config set compute/zone us-central1-a

Get sample code for this lab

Get the sample code for creating and running containers and deployments:

git clone https://github.com/googlecodelabs/orchestrate-with-kubernetes.git

cd orchestrate-with-kubernetes/kubernetes

Create a cluster with five n1-standard-1 nodes (this will take a few minutes to complete):

gcloud container clusters create bootcamp --num-nodes 5 --scopes "https://www.googleapis.com/auth/projecthosting,storage-rw"

Learn about the deployment object

Let’s get started with Deployments. First let’s take a look at the Deployment object. The explain command in kubectl can tell us about the Deployment object.

kubectl explain deployment

We can also see all of the fields using the –recursive option.

kubectl explain deployment --recursive

You can use the explain command as you go through the lab to help you understand the structure of a Deployment object and understand what the individual fields do.

kubectl explain deployment.metadata.name

Create a deployment

Update the deployments/auth.yaml cs file:

vi deployments/auth.yaml

Start the editor:

i

Change the image in the containers section of the Deployment to the following:

...

containers:

- name: auth

image: kelseyhightower/auth:1.0.0

...

Save the auth.yaml file: press <Esc> then:

:wq

Now let’s create a simple deployment. Examine the deployment configuration file:

cat deployments/auth.yaml

(Output)

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: auth

spec:

replicas: 1

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: auth

track: stable

spec:

containers:

- name: auth

image: "kelseyhightower/auth:1.0.0"

ports:

- name: http

containerPort: 80

- name: health

containerPort: 81

...

Notice how the Deployment is creating one replica and it’s using version 1.0.0 of the auth container.

When you run the kubectl create command to create the auth deployment, it will make one pod that conforms to the data in the Deployment manifest. This means we can scale the number of Pods by changing the number specified in the replicas field.

Go ahead and create your deployment object using kubectl create:

kubectl create -f deployments/auth.yaml

Once you have created the Deployment, you can verify that it was created.

kubectl get deployments

Once the deployment is created, Kubernetes will create a ReplicaSet for the Deployment. We can verify that a ReplicaSet was created for our Deployment:

kubectl get replicasets

We should see a ReplicaSet with a name like auth-xxxxxxx

Finally, we can view the Pods that were created as part of our Deployment. The single Pod is created by the Kubernetes when the ReplicaSet is created.

kubectl get pods

It’s time to create a service for our auth deployment. You’ve already seen service manifest files, so we won’t go into the details here. Use the kubectl create command to create the auth service.

kubectl create -f services/auth.yaml

Now, do the same thing to create and expose the hello Deployment.

kubectl create -f deployments/hello.yaml

kubectl create -f services/hello.yaml

And one more time to create and expose the frontend Deployment.

kubectl create secret generic tls-certs --from-file tls/

kubectl create configmap nginx-frontend-conf --from-file=nginx/frontend.conf

kubectl create -f deployments/frontend.yaml

kubectl create -f services/frontend.yaml

Note: You created a ConfigMap for the frontend.

Interact with the frontend by grabbing its external IP and then curling to it.

kubectl get services frontend

curl -ks https://<EXTERNAL-IP>

curl -ks https://35.222.2.201

And you get the hello response back.

You can also use the output templating feature of kubectl to use curl as a one-liner:

curl -ks https://`kubectl get svc frontend -o=jsonpath="{.status.loadBalancer.ingress[0].ip}"`

Scale a Deployment

Now that we have a Deployment created, we can scale it. Do this by updating the spec.replicas field. You can look at an explanation of this field using the kubectl explain command again.

kubectl explain deployment.spec.replicas

The replicas field can be most easily updated using the kubectl scale command:

kubectl scale deployment hello --replicas=5

Note: It may take a minute or so for all the new pods to start up.

After the Deployment is updated, Kubernetes will automatically update the associated ReplicaSet and start new Pods to make the total number of Pods equal 5.

Verify that there are now 5 hello Pods running:

kubectl get pods | grep hello- | wc -l

Now scale back the application:

kubectl scale deployment hello --replicas=3

Again, verify that you have the correct number of Pods.

kubectl get pods | grep hello- | wc -l

You learned about Kubernetes deployments and how to manage & scale a group of Pods.

Rolling update

Deployments support updating images to a new version through a rolling update mechanism. When a Deployment is updated with a new version, it creates a new ReplicaSet and slowly increases the number of replicas in the new ReplicaSet as it decreases the replicas in the old ReplicaSet.

Trigger a rolling update

To update your Deployment, run the following command:

kubectl edit deployment hello

Change the image in the containers section of the Deployment to the following:

...

containers:

- name: hello

image: kelseyhightower/hello:2.0.0

...

Save and exit.

Once you save out of the editor, the updated Deployment will be saved to your cluster and Kubernetes will begin a rolling update.

See the new ReplicaSet that Kubernetes creates.:

kubectl get replicaset

You can also see a new entry in the rollout history:

kubectl rollout history deployment/hello

Pause a rolling update

If you detect problems with a running rollout, pause it to stop the update. Give that a try now:

kubectl rollout pause deployment/hello

Verify the current state of the rollout:

kubectl rollout status deployment/hello

You can also verify this on the Pods directly:

kubectl get pods -o jsonpath --template='{range .items[*]}{.metadata.name}{"\t"}{"\t"}{.spec.containers[0].image}{"\n"}{end}'

Resume a rolling update

The rollout is paused which means that some pods are at the new version and some pods are at the older version. We can continue the rollout using the resume command.

kubectl rollout resume deployment/hello

When the rollout is complete, you should see the following when running the status command.

kubectl rollout status deployment/hello

(Output)

deployment "hello" successfully rolled out

Rollback an update

Assume that a bug was detected in your new version. Since the new version is presumed to have problems, any users connected to the new Pods will experience those issues.

You will want to roll back to the previous version so you can investigate and then release a version that is fixed properly.

Use the rollout command to roll back to the previous version:

kubectl rollout undo deployment/hello

Verify the roll back in the history:

kubectl rollout history deployment/hello

Finally, verify that all the Pods have rolled back to their previous versions:

kubectl get pods -o jsonpath --template='{range .items[*]}{.metadata.name}{"\t"}{"\t"}{.spec.containers[0].image}{"\n"}{end}'

Great! You learned about rolling updates for Kubernetes deployments and how to update applications without downtime.

Canary deployments

When you want to test a new deployment in production with a subset of your users, use a canary deployment. Canary deployments allow you to release a change to a small subset of your users to mitigate risk associated with new releases.

Create a canary deployment

A canary deployment consists of a separate deployment with your new version and a service that targets both your normal, stable deployment as well as your canary deployment.

First, create a new canary deployment for the new version:

cat deployments/hello-canary.yaml

(Output)

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: hello-canary

spec:

replicas: 1

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: hello

track: canary

# Use ver 1.0.0 so it matches version on service selector

version: 1.0.0

spec:

containers:

- name: hello

image: kelseyhightower/hello:2.0.0

ports:

- name: http

containerPort: 80

- name: health

containerPort: 81

...

Make sure to update version to 1.0.0 (if your version is pointing to any other)

Now create the canary deployment:

kubectl create -f deployments/hello-canary.yaml

After the canary deployment is created, you should have two deployments, hello and hello-canary. Verify it with this kubectl command:

kubectl get deployments

On the hello service, the selector uses the app:hello selector which will match pods in both the prod deployment and canary deployment. However, because the canary deployment has a fewer number of pods, it will be visible to fewer users.

Verify the canary deployment

You can verify the hello version being served by the request:

curl -ks https://`kubectl get svc frontend -o=jsonpath="{.status.loadBalancer.ingress[0].ip}"`/version

Run this several times and you should see that some of the requests are served by hello 1.0.0 and a small subset (1/4 = 25%) are served by 2.0.0.

Canary deployments in production - session affinity

In this lab, each request sent to the Nginx service had a chance to be served by the canary deployment. But what if you wanted to ensure that a user didn’t get served by the Canary deployment? A use case could be that the UI for an application changed, and you don’t want to confuse the user. In a case like this, you want the user to “stick” to one deployment or the other.

You can do this by creating a service with session affinity. This way the same user will always be served from the same version. In the example below the service is the same as before, but a new sessionAffinity field has been added, and set to ClientIP. All clients with the same IP address will have their requests sent to the same version of the hello application.

kind: Service

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

name: "hello"

spec:

sessionAffinity: ClientIP

selector:

app: "hello"

ports:

- protocol: "TCP"

port: 80

targetPort: 80

Due to it being difficult to set up an environment to test this, you don’t need to here, but you may want to use sessionAffinity for canary deployments in production.

Blue-green deployments

Rolling updates are ideal because they allow you to deploy an application slowly with minimal overhead, minimal performance impact, and minimal downtime. There are instances where it is beneficial to modify the load balancers to point to that new version only after it has been fully deployed. In this case, blue-green deployments are the way to go.

Kubernetes achieves this by creating two separate deployments; one for the old “blue” version and one for the new “green” version. Use your existing hello deployment for the “blue” version. The deployments will be accessed via a Service which will act as the router. Once the new “green” version is up and running, you’ll switch over to using that version by updating the Service.

A major downside of blue-green deployments is that you will need to have at least 2x the resources in your cluster necessary to host your application. Make sure you have enough resources in your cluster before deploying both versions of the application at once.

The service

Use the existing hello service, but update it so that it has a selector app:hello, version: 1.0.0. The selector will match the existing “blue” deployment. But it will not match the “green” deployment because it will use a different version.

First update the service:

kubectl apply -f services/hello-blue.yaml

Updating using Blue-Green Deployment

n order to support a blue-green deployment style, we will create a new “green” deployment for our new version. The green deployment updates the version label and the image path.

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: hello-green

spec:

replicas: 3

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: hello

track: stable

version: 2.0.0

spec:

containers:

- name: hello

image: kelseyhightower/hello:2.0.0

ports:

- name: http

containerPort: 80

- name: health

containerPort: 81

resources:

limits:

cpu: 0.2

memory: 10Mi

livenessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /healthz

port: 81

scheme: HTTP

initialDelaySeconds: 5

periodSeconds: 15

timeoutSeconds: 5

readinessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /readiness

port: 81

scheme: HTTP

initialDelaySeconds: 5

timeoutSeconds: 1

Create the green deployment:

kubectl create -f deployments/hello-green.yaml

Once you have a green deployment and it has started up properly, verify that the current version of 1.0.0 is still being used:

curl -ks https://`kubectl get svc frontend -o=jsonpath="{.status.loadBalancer.ingress[0].ip}"`/version

Now, update the service to point to the new version:

kubectl apply -f services/hello-green.yaml

With the service is updated, the “green” deployment will be used immediately. You can now verify that the new version is always being used.

curl -ks https://`kubectl get svc frontend -o=jsonpath="{.status.loadBalancer.ingress[0].ip}"`/version

You did it! You learned about blue-green deployments and how to deploy updates to applications that need to switch versions all at once.

Blue-Green Rollback

If necessary, you can roll back to the old version in the same way. While the “blue” deployment is still running, just update the service back to the old version.

kubectl apply -f services/hello-blue.yaml

Once you have updated the service, your rollback will have been successful. Again, verify that the right version is now being used:

curl -ks https://`kubectl get svc frontend -o=jsonpath="{.status.loadBalancer.ingress[0].ip}"`/version

You did it! You learned about blue-green deployments and how to deploy updates to applications that need to switch versions all at once.

Build a Slack Bot with Node.js on Kubernetes

Get the sample code

In Cloud Shell on the command-line, run the following command to clone the GitHub repository:

git clone https://github.com/googlecodelabs/cloud-slack-bot.git

Change directory into cloud-slack-bot/start:

cd cloud-slack-bot/start

Install the Node.js dependencies, including Botkit:

npm install

Run the sample app

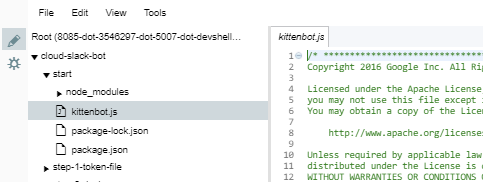

In Cloud Shell, edit the kittenbot.js file and enter your Slack bot token. If it is no longer in your clipboard, you can get it from the bot custom integration configuration page. You can use any editor you like, such as emacs or vim. This lab uses the code editor feature of Cloud Shell for simplicity.

Open the Cloud Shell code editor:

Open the kittenbot.js file by going to cloud-slack-bot/start/kittenbot.js:

Replace your-slack-token (Bot User OAuth Access Token) with the Slack token you copied:

var Botkit = require('botkit')

var controller = Botkit.slackbot({debug: false})

controller

.spawn({

token: 'your-slack-token' // Edit this line!

})

.startRTM(function (err) {

if (err) {

throw new Error(err)

}

})

controller.hears(

['hello', 'hi'], ['direct_message', 'direct_mention', 'mention'],

function (bot, message) { bot.reply(message, 'Meow. :smile_cat:') })

Then save the file with Ctrl-s or File > Save.

Note: As you can see in the file, kittenbot will only respond to “hi” and “hello” greetings. Make sure you enter one of those greetings to see it respond.

In Cloud Shell run your bot:

node kittenbot.js

You may see errors in Cloud Shell, but they won’t affect the lab. It’s OK to keep going.

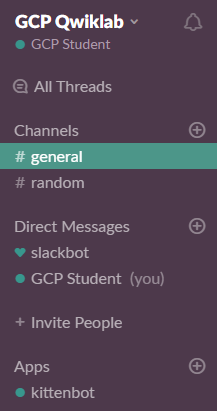

In your Slack workspace, you should now see that kittenbot is online. You may need to refresh your browser. Do the following to interact with it:

Click on the + next to Direct Messages:

Load Slack token from a file

Hard-coding the Slack token in the source code makes it likely to accidentally expose your token by publishing it to version control or embedding it in a docker image. Instead, use Kubernetes Secrets to store tokens.

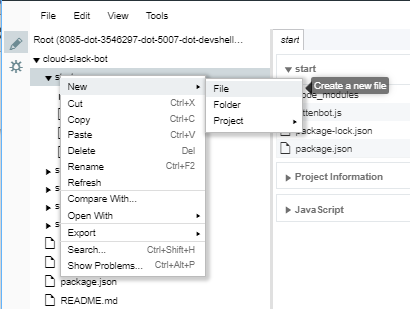

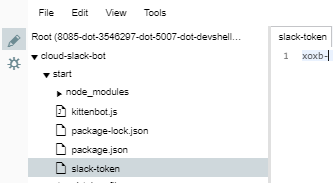

You will now write your token to a file called slack-token. This filename is in the .gitignore to prevent accidentally checking it in to version control.

Create a new file in the start directory called slack-token file. (To right-click on a Chromebook: press the touchpad with two fingers, or press Alt while clicking with one finger.)

Copy your token from kittenbot.js or the bot configuration page, paste it into the slack-token file, then Save.

Edit the kittenbot.js file to load the Slack token specified by the slack_token_path environment variable:

var Botkit = require('botkit')

var fs = require('fs') // NEW: Add this require (for loading from files).

var controller = Botkit.slackbot({debug: false})

// START: Load Slack token from file.

if (!process.env.slack_token_path) {

console.log('Error: Specify slack_token_path in environment')

process.exit(1)

}

fs.readFile(process.env.slack_token_path, function (err, data) {

if (err) {

console.log('Error: Specify token in slack_token_path file')

process.exit(1)

}

data = String(data)

data = data.replace(/\s/g, '')

controller

.spawn({token: data})

.startRTM(function (err) {

if (err) {

throw new Error(err)

}

})

})

// END: Load Slack token from file.

controller.hears(

['hello', 'hi'], ['direct_message', 'direct_mention', 'mention'],

function (bot, message) { bot.reply(message, 'Meow. :smile_cat:') })

Go back to the Cloud Console and run your bot:

slack_token_path=./slack-token node kittenbot.js

You should see the bot online again in Slack and be able to chat with it. After testing it out, press Ctrl-c to shut down the bot.

Create a Docker container image

Docker provides a way to containerize your bot. A Docker image bundles all of your dependencies (even the compiled ones) so that it can run in a lightweight sandbox.

Building a Docker image

First, create a file called Dockerfile.

Then add the following definition, which describes how to build your Docker image.

FROM node:10.14

COPY package.json /src/package.json

WORKDIR /src

RUN npm install

COPY kittenbot.js /src

CMD ["node", "/src/kittenbot.js"]

Save this file.

A Dockerfile is a recipe for a Docker image. This one layers on top of the Node.js base image found on the Docker hub, copies package.json to the image and installs the dependencies listed in it, copies the kittenbot.js file to the image, and tells Docker that it should run the Node.js server when the image starts.

Go back to the Cloud Shell and run this command to save your project ID to the environment variable PROJECT_ID. Commands in this lab will use this variable as $PROJECT_ID.

export PROJECT_ID=$(gcloud config list --format 'value(core.project)')

Build the image by running the docker build command. (This command takes about 4 minutes to complete. It has to download the base image and Node.js dependencies.)

docker build -t gcr.io/${PROJECT_ID}/slack-codelab:v1 .

While the Docker image is building, try this out this Extra Credit exercise to get a webhook to use later in the lab.

Extra Credit: Create an incoming webhook to Slack

An incoming webhook is an easy way to send Slack notifications from another service or app without having to worry about a persistent connection for two-way communication like with a bot user. Create one now:

Go to the Slack apps management page.

Click on your app Kittenbot, and then in the left panel, click Incoming Webhooks.

Toggle Activate Incoming Webhooks to On.

At the top, there’s a message “You’ve changed the permissions scopes …”. Click click here.

From the Post to dropdown, select the Slack channel #general for messages to post to.

Click Authorize.

Copy the webhook URL and save it to your computer. You’ll come back to this in a later step.

Testing a Docker image locally

Go back to Cloud Shell to test the image locally with the following command. It will run a Docker container as a daemon from the newly-created container image:

docker run -d \

-v $(pwd)/:/config \

-e slack_token_path=/config/slack-token \

gcr.io/${PROJECT_ID}/slack-codelab:v1

This command also mounts the current directory as a volume inside the container to give it access to the slack-token file. You should see that kittenbot is online again.

Here’s the full documentation for the docker run command: https://docs.docker.com/engine/reference/run/

Frequently asked question: How do I get the project ID from the gcloud command-line tool?

Pushing a Docker image to Google Container Registry

Now that the image works as intended, push it to the Google Container Registry, a private repository for your Docker images accessible from every Google Cloud project (but also from outside Google Cloud Platform).

Push the Docker image to Google Container Registry from Cloud Shell:

gcloud docker -- push gcr.io/${PROJECT_ID}/slack-codelab:v1

(This command takes about 5 minutes to complete.)

Extra Credit: Testing an incoming webhook

While waiting for the image to upload, use the incoming webhook to send a notification to Slack.

In Cloud Shell, click the + button tab to add a new Cloud Shell session:

Go back to the incoming webhook you created. (If you closed that browser tab you can get back to there from the Slack apps management page, click your app, Kittenbot, and in the left pand, click Incoming Webhooks.)

From the Incoming Webhooks page, click the Copy button for the “Sample curl request to post to a channel”, and paste it into the new Cloud Shell Session.

This will run curl to send an HTTP request with your message to Slack.

In your Slack app, in the #general channel, look for a message from kittenbot.

This demonstrates that anywhere that you can send an HTTP request, you can send a message to Slack. This is a really easy way to integrate your own apps and services with Slack notifications.

For more complicated messages, test out the JSON request first in the Slack message builder.

Viewing images in Google Container Registry

When the image upload completes, you can see it listed in the Google Cloud Console. Under the Tools section, click on Container Registry > Images.

You now have a project-wide Docker image available which Kubernetes can access and orchestrate.

Notice a generic domain was used for the registry (gcr.io). You can also be more specific about which zone and bucket to use. Details are documented here: https://cloud.google.com/container-registry/#pushing_to_the_registry

If you’re curious, you can navigate through the container images as they are stored in Google Cloud Storage by following this link: https://console.cloud.google.com/storage/browser/.

Frequently Asked Questions:

-

Troubleshooting Google Container Registry (Unable to ping registry endpoint).

-

“Repository does not exist” error when doing gcloud docker push command.

Create a Kubernetes cluster on Kubernetes Engine

Now that the Docker image is in Google Container Registry, you can run the gcloud docker – pull command to save this image on any machine and run it with the Docker command-line tool.

If you want to make sure your bot keeps running after it is started, you’ll have to run another service to monitor your Docker container to restart it if it stops. This gets harder if you want to make sure the bot keeps running even if the machine it is running on fails.

Kubernetes solves these problems. You tell it that you want there to always be a replica of your bot running, and the Kubernetes master will keep that target state. It starts the bot up when there aren’t enough running, and shuts bot replicas down when there are too many.

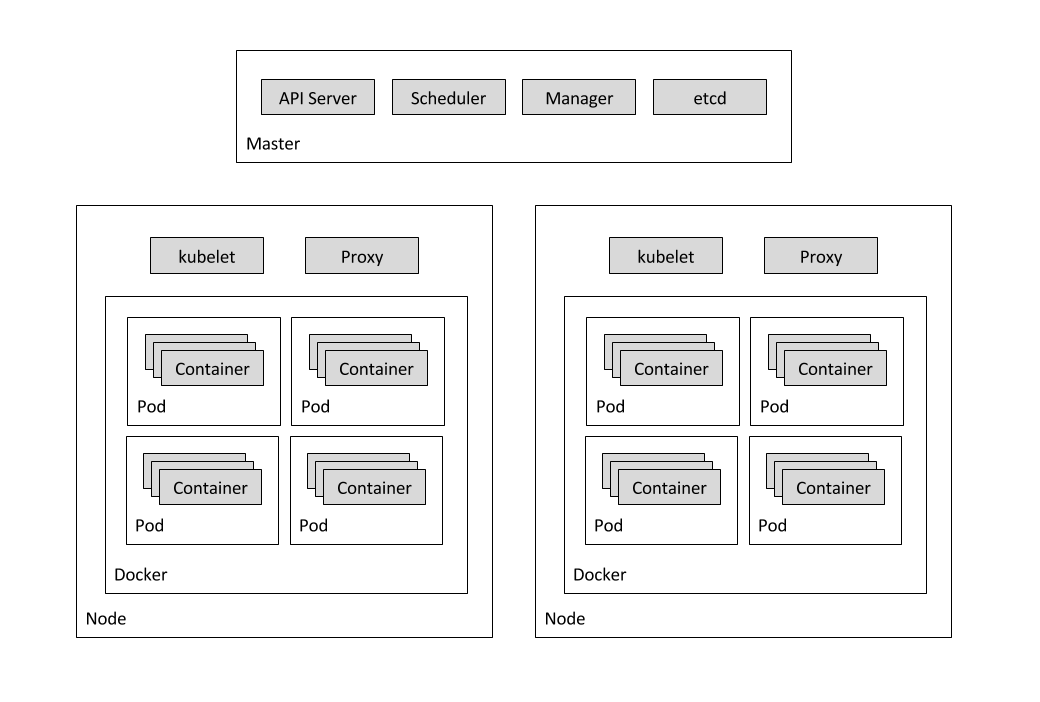

A Kubernetes Engine cluster is a managed Kubernetes cluster. It consists of a Kubernetes master API server hosted by Google and a set of worker nodes. The worker nodes are Compute Engine virtual machines.

Return to the first Cloud Shell if you tried the extra credit.

Create a cluster with two n1-standard-1 nodes (this will take a few minutes to complete):

gcloud container clusters create my-cluster \

--num-nodes=2 \

--zone=us-central1-f \

--machine-type n1-standard-1

(Output)

Creating cluster my-cluster...done.

Created [https://container.googleapis.com/v1/projects/PROJECT_ID/zones/us-central1-f/clusters/my-cluster].

kubeconfig entry generated for my-cluster.

NAME ZONE MACHINE_TYPE NUM_NODES STATUS

my-cluster us-central1-f n1-standard-1 2 RUNNING

Alternatively, you could create this cluster via the Cloud Console:

Kubernetes Engine > Kubernetes clusters > Create cluster.

If you use the Cloud Console to create the cluster, run gcloud container clusters get-credentials my-cluster --zone=us-central1-f to authenticate Cloud Shell with the cluster credentials.

This command creates the cluster and authenticates the Kubernetes command-line tool, kubectl, with the new cluster’s credentials.

You should now have a fully-functioning Kubernetes cluster powered by Kubernetes Engine. You’ll see it in the Cloud Console in Kubernetes Engine > Kubernetes clusters.

Each node in the cluster is a Compute Engine instance provisioned with Kubernetes and Docker binaries. If you are curious, you can list all Compute Engine instances in the project:

gcloud compute instances list

(Output)

NAME ZONE MACHINE_TYPE INTERNAL_IP EXTERNAL_IP STATUS

gke-my-cl...16 us-central1-f n1-standard-1 10.240.0.2 146.148.100.240 RUNNING

gke-my-cl...34 us-central1-f n1-standard-1 10.240.0.3 104.154.36.108 RUNNING

For the rest of this lab you’ll use kubectl, the Kubernetes command-line tool, to configure and run your bot.

Create a Deployment

First, create a Secret in Kubernetes to store the Slack token and make it available to the container:

kubectl create secret generic slack-token --from-file=./slack-token

(Output)

secret "slack-token" created

To deploy your own containerized application to the Kubernetes cluster you need to configure a Deployment, which describes how to configure the container and provide a replication controller to keep the bot running.

In the Cloud Shell Code Editor, create a file called slack-codelab-deployment.yaml.

Enter the following deployment definition, replacing PROJECT_ID with your Project ID:

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: slack-codelab

spec:

replicas: 1

strategy:

type: Recreate

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: slack-codelab

spec:

containers:

- name: master

image: gcr.io/PROJECT_ID/slack-codelab:v1 # Replace PROJECT_ID

# with your project ID.

volumeMounts:

- name: slack-token

mountPath: /etc/slack-token

env:

- name: slack_token_path

value: /etc/slack-token/slack-token

volumes:

- name: slack-token

secret:

secretName: slack-token

Save the file, File > Save.

Now you can create the Deployment by running kubectl create in Cloud Shell:

kubectl create -f slack-codelab-deployment.yaml --record

(Output)

deployment "slack-codelab" created

Since you used the –record option, you can view the commands applied to this deployment as the “change-cause” in the rollout history:

kubectl rollout history deployment/slack-codelab

(Output)

deployments "slack-codelab":

REVISION CHANGE-CAUSE

1 kubectl create -f slack-codelab-deployment.yaml --record

See what the kubectl create command made. Re-run this command until the status shows Running.

kubectl get pods

This should take about 30 seconds to 1 minute

(Output)

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

slack-codelab-2890463383-1ss4a 1/1 Running 0 3m

The last things you need to do:

- Re-run kubectl get pods until the status for the pod shows Running.

- Go to Slack, and see that kittenbot is back online.

- Say hello to kittenbot one last time in a direct message.

Frequently asked questions:

Extra Credit: Update your bot to a new version

This extra credit section should take you about 10 minutes to complete. So you’d like the bot to do more than just say “meow”. How do you deploy a new version of something that is already running on Kubernetes? First, you need to modify the application. Botkit can handle conversations. With these, the bot can request more information and react to messages beyond a one word reply.

Edit the kittenbot.js file in the code editor. Add this new kitten emoji delivery code to the bottom of the file:

// ...

// START: listen for cat emoji delivery

var maxCats = 20

var catEmojis = [

':smile_cat:',

':smiley_cat:',

':joy_cat:',

':heart_eyes_cat:',

':smirk_cat:',

':kissing_cat:',

':scream_cat:',

':crying_cat_face:',

':pouting_cat:',

':cat:',

':cat2:',

':leopard:',

':lion_face:',

':tiger:',

':tiger2:'

]

controller.hears(

['cat', 'cats', 'kitten', 'kittens'],

['ambient', 'direct_message', 'direct_mention', 'mention'],

function (bot, message) {

bot.startConversation(message, function (err, convo) {

if (err) {

console.log(err)

return

}

convo.ask('Does someone need a kitten delivery? Say YES or NO.', [

{

pattern: bot.utterances.yes,

callback: function (response, convo) {

convo.say('Great!')

convo.ask('How many?', [

{

pattern: '[0-9]+',

callback: function (response, convo) {

var numCats =

parseInt(response.text.replace(/[^0-9]/g, ''), 10)

if (numCats === 0) {

convo.say({

'text': 'Sorry to hear you want zero kittens. ' +

'Here is a dog, instead. :dog:',

'attachments': [

{

'fallback': 'Chihuahua Bubbles - https://youtu.be/s84dBopsIe4',

'text': '<https://youtu.be/s84dBopsIe4|' +

'Chihuahua Bubbles>!'

}

]

})

} else if (numCats > maxCats) {

convo.say('Sorry, ' + numCats + ' is too many cats.')

} else {

var catMessage = ''

for (var i = 0; i < numCats; i++) {

catMessage = catMessage +

catEmojis[Math.floor(Math.random() * catEmojis.length)]

}

convo.say(catMessage)

}

convo.next()

}

},

{

default: true,

callback: function (response, convo) {

convo.say(

"Sorry, I didn't understand that. Enter a number, please.")

convo.repeat()

convo.next()

}

}

])

convo.next()

}

},

{

pattern: bot.utterances.no,

callback: function (response, convo) {

convo.say('Perhaps later.')

convo.next()

}

},

{

default: true,

callback: function (response, convo) {

// Repeat the question.

convo.repeat()

convo.next()

}

}

])

})

})

// END: listen for cat emoji delivery

Then Save the file.

You can test this out in Cloud Shell using the same command as before, but you’ll see two responses since the bot is still running in your Kubernetes cluster.

Next, build a new container image with an incremented tag (v2 in this case):

docker build -t gcr.io/${PROJECT_ID}/slack-codelab:v2 .

Push the image to Google Container Registry:

gcloud docker -- push gcr.io/${PROJECT_ID}/slack-codelab:v2

Building and pushing this updated image should be much quicker, taking full advantage of caching.

As you did with the first version of the kitten bot, you can test locally using the node command and the docker command. You can skip those steps and push the new version to the cluster.

Now you’re ready for Kubernetes to update the deployment to the new version of the application.

Edit the line in the slack-codelab-deployment.yaml file defining which image to use:

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: slack-codelab

spec:

replicas: 1

strategy:

type: Recreate

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: slack-codelab

spec:

containers:

- name: master

image: gcr.io/PROJECT_ID/slack-codelab:v2 # Update this to v2.

# Replace PROJECT_ID

# with your project ID.

volumeMounts:

- name: slack-token

mountPath: /etc/slack-token

env:

- name: slack_token_path

value: /etc/slack-token/slack-token

volumes:

- name: slack-token

secret:

secretName: slack-token

Save the file.

Now, to apply this change to the running Deployment, run this command to update the deployment to use the v2 image:

kubectl apply -f slack-codelab-deployment.yaml

(Output)

deployment "slack-codelab" configured

Use this code to see that Kubernetes has shut down the pod running the previous version and started a new pod that is running the new image:

kubectl get pods

(Output)

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

slack-codelab-2890463383-mqy5l 1/1 Terminating 0 17m

slack-codelab-3059677337-b41r0 1/1 Running 0 7s

Deployment Strategies: Since the deployment strategy was specified to “recreate” when you created the deployment, Kubernetes makes sure the old instances are shut down before creating a new one. This strategy is used because:

- we don’t mind a few seconds of downtime and

- we don’t want two custom integration bots running at the same time. Alternatively, a rolling update strategy could have been used, which ensures that new versions are running before shutting down the old versions. This would be ideal if creating a Slack App used by multiple teams.

See the changed deployment:

kubectl rollout history deployment/slack-codelab

(Output)

deployments "slack-codelab":

REVISION CHANGE-CAUSE

1 kubectl create -f slack-codelab-deployment.yaml --record

2 kubectl apply -f slack-codelab-deployment.yaml

Go back to Slack and type a message to kittenbot that mentions “kitten” and see it join the conversation.

You just updated a Slack bot running on Kubernetes to a new version.

Using Kubernetes Engine to Deploy Apps with Regional Persistent Disks

Overview

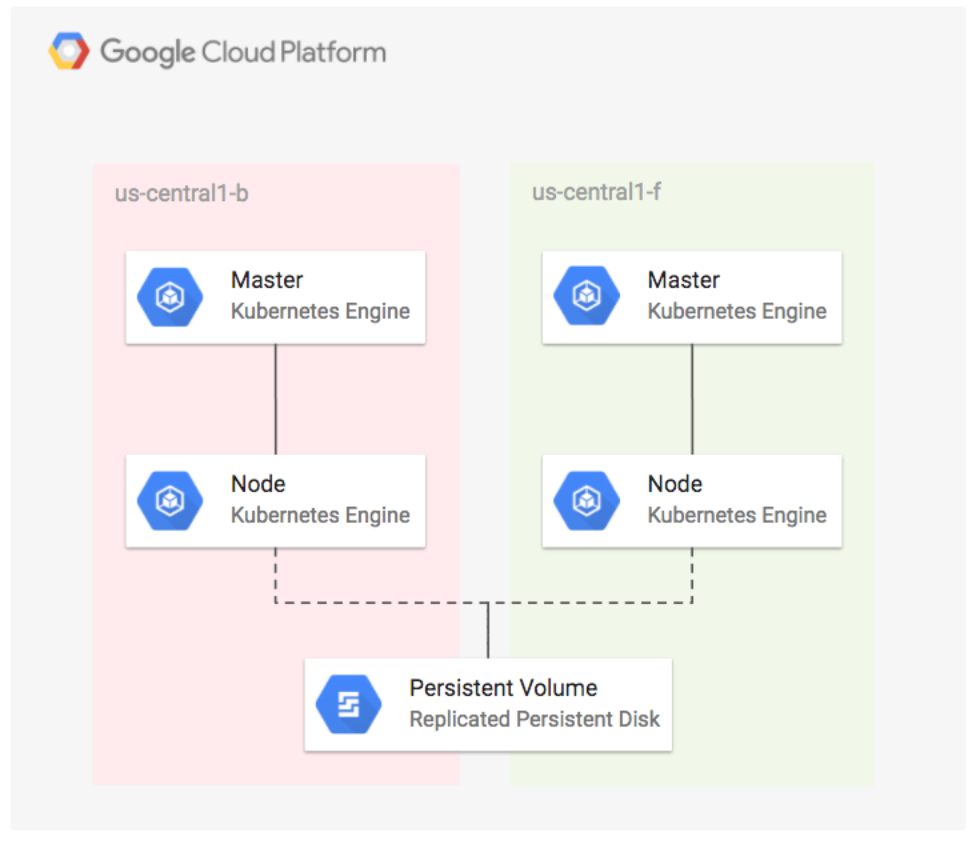

In this lab you will learn how to configure a highly available application by deploying WordPress using regional persistent disks on Kubernetes Engine. Regional persistent disks provide synchronous replication between two zones, which keeps your application up and running in case there is an outage or failure in a single zone. Deploying a Kubernetes Engine Cluster with regional persistent disks will make your application more stable, secure, and reliable.

What you’ll do

- Create a regional Kubernetes Engine cluster.

- Create a Kubernetes StorageClass resource that is configured for replicated zones.

- Deploy WordPress with a regional disk that uses the StorageClass.

- Simulate a zone failure by deleting a node.

- Verify that the WordPress app and data migrate successfully to another replicated zone.

Prerequisites

This is an advanced lab. Before taking it, you should be familiar with at least the basics of Kubernetes and WordPress. Here are some Qwiklabs that can get you up to speed:

- Kubernetes Engine: Qwik Start

- Running WordPress on App Engine Flexible Environment

- Hello Node Kubernetes

Once you’re prepared, scroll down to get your lab environment set up.

Creating the Regional Kubernetes Engine Cluster

Open a new Cloud Shell session. You will first create a regional Kubernetes Engine cluster that spans three zones in the us-west1 region. First, fetch the server configuration for the us-west1 region and export environment variables by running:

CLUSTER_VERSION=$(gcloud container get-server-config --region us-west1 --format='value(validMasterVersions[0])')

export CLOUDSDK_CONTAINER_USE_V1_API_CLIENT=false

Now create a standard Kubernetes Engine cluster (this will take a little while, ignore any warnings about node auto repairs):

gcloud container clusters create repd \

--cluster-version=${CLUSTER_VERSION} \

--machine-type=n1-standard-4 \

--region=us-west1 \

--num-nodes=1 \

--node-locations=us-west1-a,us-west1-b,us-west1-c

Example Output:

Creating cluster repd...done.

Created [https://container.googleapis.com/v1beta1/projects/qwiklabs-gcp-e8f5f22705c770ab/zones/us-west1/clusters/repd].

To inspect the contents of your cluster, go to: https://console.cloud.google.com/kubernetes/workload_/gcloud/us-west1/repd?project=qwiklabs-gcp-e8f5f22705c770ab

kubeconfig entry generated for repd.

NAME LOCATION MASTER_VERSION MASTER_IP MACHINE_TYPE NODE_VERSION NUM_NODES STATUS

repd us-west1 1.12.6-gke.7 35.247.50.133 n1-standard-4 1.12.6-gke.7 3 RUNNING

You just created a regional cluster (located in us-west1) with one node in each zone (us-west1-a,us-west1-b,us-west1-c). Navigate to Compute Engine from the left-hand menu to view your instances:

Deploying the App with a Regional Disk

Now that you have your Kubernetes cluster running, you’ll do the following three things:

- Install Helm (a toolset for managing Kubernetes packages)

- Create the Kubernetes StorageClass that is used by the regional persistent disk

- Deploy WordPres

Install and initialize Helm to install the chart package

The chart package, which is installed with Helm, contains everything you need to run WordPress.

- Install Helm locally in your Cloud Shell instance by running:

curl https://raw.githubusercontent.com/kubernetes/helm/master/scripts/get > get_helm.sh chmod 700 get_helm.sh ./get_helm.shInitialize Helm: ``` kubectl create serviceaccount tiller –namespace kube-system

kubectl create clusterrolebinding tiller-cluster-rule \ –clusterrole=cluster-admin \ –serviceaccount=kube-system:tiller helm init –service-account=tiller until (helm version –tiller-connection-timeout=1 >/dev/null 2>&1); do echo “Waiting for tiller install…”; sleep 2; done && echo “Helm install complete”

Helm is now installed in your cluster.

#### Create the StorageClass

Next you'll create the StorageClass used by the chart to define the zones of the regional disk. The zones listed in the StorageClass will match the zones of the Kubernetes Engine cluster.

Create a StorageClass for the regional disk by running:

kubectl apply -f - «EOF kind: StorageClass apiVersion: storage.k8s.io/v1 metadata: name: repd-west1-a-b-c provisioner: kubernetes.io/gce-pd parameters: type: pd-standard replication-type: regional-pd zones: us-west1-a, us-west1-b, us-west1-c EOF

Example Output:

storageclass “repd-west1-a-b-c” created

You now have a StorageClass that is capable of provisioning PersistentVolumes that are replicated across the us-west1-a, us-west1-b and us-west1-c zones.

List the available `storageclass` with:

kubectl get storageclass

Example Output:

NAME PROVISIONER AGE repd-west1-a-b-c kubernetes.io/gce-pd 26s standard (default) kubernetes.io/gce-pd 1h

### Create Persistent Volume Claims

In this section, you will create persistentvolumeclaims for your application.

Create data-wp-repd-mariadb-0 PVC with standard StorageClass.

kubectl apply -f - «EOF kind: PersistentVolumeClaim apiVersion: v1 metadata: name: data-wp-repd-mariadb-0 namespace: default labels: app: mariadb component: master release: wp-repd spec: accessModes: - ReadOnlyMany resources: requests: storage: 8Gi storageClassName: standard EOF

Create `wp-repd-wordpress` PVC with `repd-west1-a-b-c` StorageClass.

kubectl apply -f - «EOF kind: PersistentVolumeClaim apiVersion: v1 metadata: name: wp-repd-wordpress namespace: default labels: app: wp-repd-wordpress chart: wordpress-5.7.1 heritage: Tiller release: wp-repd spec: accessModes: - ReadOnlyMany resources: requests: storage: 200Gi storageClassName: repd-west1-a-b-c EOF

List the available `persistentvolumeclaims` with:

kubectl get persistentvolumeclaims

Example Output:

NAME STATUS VOLUME CAPACITY ACCESS MODES STORAGECLASS AGE data-wp-repd-mariadb-0 Bound pvc-8a10ed04-56ca-11e9-a020-42010a8a003d 8Gi ROX standard 21m wp-repd-wordpress Bound pvc-ad5ddb0b-56ca-11e9-9af5-42010a8a0047 200Gi ROX repd-west1-a-b-c 20m

Deploy WordPress

Now that we have our StorageClass configured, Kubernetes automatically attaches the persistent disk to an appropriate node in one of the available zones.

1. Deploy the WordPress chart that is configured to use the StorageClass that you created earlier:

helm install –name wp-repd \ –set smtpHost= –set smtpPort= –set smtpUser= \ –set smtpPassword= –set smtpUsername= –set smtpProtocol= \ –set persistence.storageClass=repd-west1-a-b-c \ –set persistence.existingClaim=wp-repd-wordpress \ –set persistence.accessMode=ReadOnlyMany \ stable/wordpress

Output:

NAME: wp-repd LAST DEPLOYED: Fri May 24 09:14:55 2019 NAMESPACE: default STATUS: DEPLOYED

RESOURCES: ==> v1/ConfigMap NAME DATA AGE wp-repd-mariadb 1 1s wp-repd-mariadb-tests 1 1s

==> v1/Deployment NAME READY UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE wp-repd-wordpress 0/1 1 0 1s

==> v1/Pod(related) NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE wp-repd-mariadb-0 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 1s wp-repd-wordpress-7889b789f-l2skn 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 1s

==> v1/Secret NAME TYPE DATA AGE wp-repd-mariadb Opaque 2 1s wp-repd-wordpress Opaque 1 1s

==> v1/Service

NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE

wp-repd-mariadb ClusterIP 10.23.249.165

==> v1beta1/StatefulSet NAME READY AGE wp-repd-mariadb 0/1 1s

NOTES:

- Get the WordPress URL:

NOTE: It may take a few minutes for the LoadBalancer IP to be available. Watch the status with: ‘kubectl get svc –namespace default -w wp-repd-wordpress’ export SERVICE_IP=$(kubectl get svc –namespace default wp-repd-wordpress –template “”) echo “WordPress URL: http://$SERVICE_IP/” echo “WordPress Admin URL: http://$SERVICE_IP/admin”

- Login with the following credentials to see your blog

echo Username: user echo Password: $(kubectl get secret –namespace default wp-repd-wordpress -o jsonpath=”{.data.wordpress-password}” | base64 –decode)

2. List out available wordpress pods:

kubectl get pods

Example Output:

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE wp-repd-mariadb-79444cd49b-lx8jq 1/1 Running 0 35m wp-repd-wordpress-7654c85b66-gz6nd 1/1 Running 0 35m

3. Run the following command which waits for the service load balancer's external IP address to be created:

while [[ -z $SERVICE_IP ]]; do SERVICE_IP=$(kubectl get svc wp-repd-wordpress -o jsonpath=’{.status.loadBalancer.ingress[].ip}’); echo “Waiting for service external IP…”; sleep 2; done; echo http://$SERVICE_IP/admin

4. Verify that the persistent disk was created:

while [[ -z $PV ]]; do PV=$(kubectl get pvc wp-repd-wordpress -o jsonpath=’{.spec.volumeName}’); echo “Waiting for PV…”; sleep 2; done

kubectl describe pv $PV

### Simulating a zone failure

Next you will simulate a zone failure and watch Kubernetes move your workload to the other zone and attach the regional disk to the new node.

1. Obtain the current node of the WordPress pod:

NODE=$(kubectl get pods -l app=wp-repd-wordpress -o jsonpath=’{.items..spec.nodeName}’)

ZONE=$(kubectl get node $NODE -o jsonpath=”{.metadata.labels[‘failure-domain.beta.kubernetes.io/zone’]}”)

IG=$(gcloud compute instance-groups list –filter=”name~gke-repd-default-pool zone:(${ZONE})” –format=’value(name)’)

echo “Pod is currently on node ${NODE}”

echo “Instance group to delete: ${IG} for zone: ${ZONE}”

Example Output:

Pod is currently on node gke-repd-default-pool-b8cf37cd-bc5q Instance group to delete: gke-repd-default-pool-b8cf37cd-grp for zone: us-west1-c

You can also verify it with:

kubectl get pods -l app=wp-repd-wordpress -o wide

Example Output:

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE IP NODE wp-repd-wordpress-7654c85b66-gz6nd 1/1 Running 0 1h 10.20.0.11 gke-repd-default-pool-b8cf37cd-bc5q

Take note of `Node` column. You are going to delete this node to simulate the zone failure.

2. Now run the following to delete the instance group for the node where the WordPress pod is running, click **Y** to continue deleting:

gcloud compute instance-groups managed delete ${IG} –zone ${ZONE}

Kubernetes is now detecting the failure and migrates the pod to a node in another zone.

3. Verify that both the WordPress pod and the persistent volume migrated to the node that is in the other zone:

kubectl get pods -l app=wp-repd-wordpress -o wide

Example Output:

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE IP NODE wp-repd-wordpress-7654c85b66-xqb78 1/1 Running 0 1m 10.20.1.14 gke-repd-default-pool-9da1b683-h70h

Make sure the node that is displayed is different from the node in the previous step.

4. Once the new service has a Running status, open the WordPress admin page in your browser from the link displayed in the command output:

echo http://$SERVICE_IP/admin

You have attached a regional persistent disk to a node that is in a different zone.

## NGINX Ingress Controller on Google Kubernetes Engine

### Set a zone

Before creating a Kubernetes cluster, we'll have to set a default computing zone for our GCP project. Run the following command to see a [list of GCP zones](https://cloud.google.com/compute/docs/regions-zones/):

gcloud compute zones list

Now run the following command to set your zone (in this case to us-central1-a):

gcloud config set compute/zone us-central1-a

### Create a Kubernetes cluster

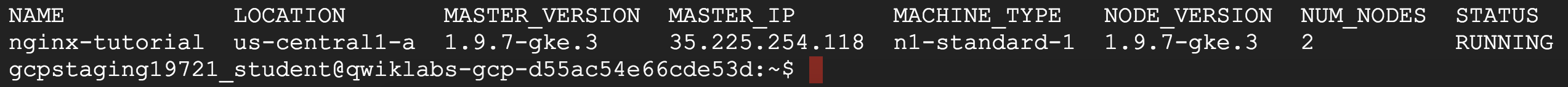

Now that our zone is configured, let's deploy a Kubernetes Engine cluster. Run the following command to create a cluster named nginx-tutorial that's made up of two nodes (or worker machines):

gcloud container clusters create nginx-tutorial –num-nodes 2

It will take a few minutes for this command to complete. Continue when you get a similar output in Cloud Shell:

### Install Helm

Now that we have our Kubernetes cluster up and running, let's install [Helm](https://helm.sh/). Helm is a tool that streamlines Kubernetes application installation and management. You can think of it like apt, yum, or homebrew for Kubernetes. Using helm charts is recommended, since they are maintained and typically kept up-to-date by the Kubernetes community. Helm has two parts: a client (helm) and a server (tiller):

* **Tiller** runs inside your Kubernetes cluster and manages releases (installations) of your Helm Charts.

* **Helm** runs on your laptop, CI/CD, or in this case, the Cloud Shell.

Helm comes preconfigured with an installer script that automatically grabs the latest version of the Helm client and installs it locally. Fetch the script by running the following command:

curl https://raw.githubusercontent.com/kubernetes/helm/master/scripts/get > get_helm.sh

Next, run the following commands to get the Helm client installed:

chmod 700 get_helm.sh ./get_helm.sh

Now initialize helm:

helm init

Great! You now have the latest copy of the Helm client installed and ready for use in your Cloud Shell environment.

### Installing Tiller

Starting with Kubernetes v1.8+, [RBAC](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Role-based_access_control) is enabled by default. Prior to installing tiller you need to ensure that you have the correct ServiceAccount and ClusterRoleBinding configured for the tiller service. This allows tiller to be able to install services in the default namespace.

Run the following commands to install the server-side tiller to the Kubernetes cluster with RBAC enabled:

kubectl create serviceaccount –namespace kube-system tiller

kubectl create clusterrolebinding tiller-cluster-rule –clusterrole=cluster-admin –serviceaccount=kube-system:tiller

kubectl patch deploy –namespace kube-system tiller-deploy -p ‘{“spec”:{“template”:{“spec”:{“serviceAccount”:”tiller”}}}}’

Now initialize Helm with your newly-created service account:

helm init –service-account tiller –upgrade

You can also confirm that tiller is running by checking for the tiller-deploy Deployment in the kube-system namespace. Run the following command to do so:

kubectl get deployments -n kube-system

The output should have a tiller-deploy Deployment as shown below:

NAME DESIRED CURRENT UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE event-exporter-v0.1.7 1 1 1 1 13m heapster-v1.4.3 1 1 1 1 13m kube-dns 2 2 2 2 13m kube-dns-autoscaler 1 1 1 1 13m kubernetes-dashboard 1 1 1 1 13m l7-default-backend 1 1 1 1 13m tiller-deploy 1 1 1 1 4m

### Deploy an application in Kubernetes Engine

Now that you have Helm configured, let's deploy a simple web-based application from the Google Cloud Repository. This application will be used as the backend for the Ingress.

From the Cloud Shell, run the following command:

kubectl run hello-app –image=gcr.io/google-samples/hello-app:1.0 –port=8080

Your output should resemble the following:

deployment “hello-app” created

Now expose the hello-app Deployment as a Service by running the following command:

kubectl expose deployment hello-app

Your output should resemble the following:

service “hello-app” exposed

### Deploying the NGINX Ingress Controller via Helm

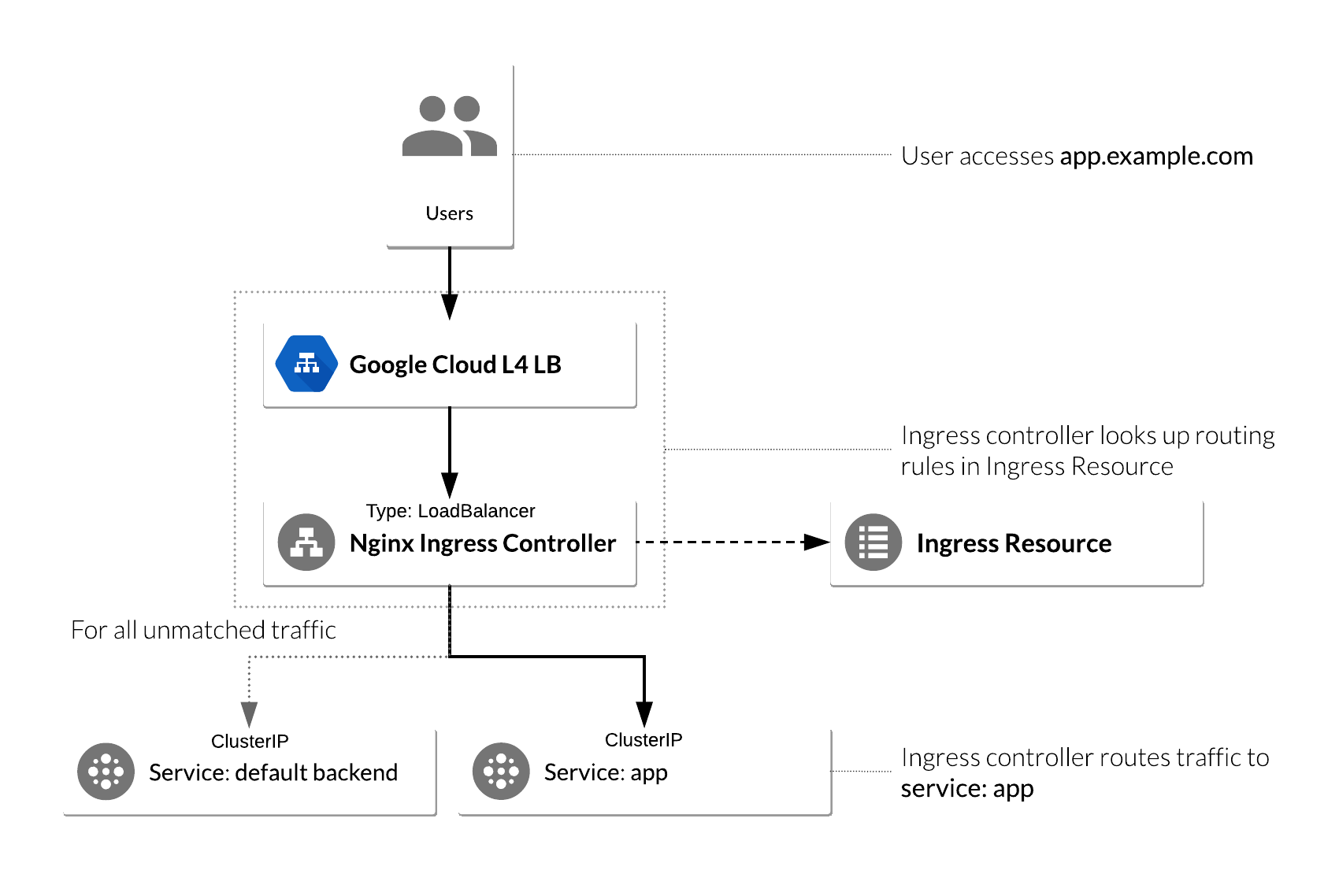

The Kubernetes platform gives administrators flexibility when it comes to Ingress Controllers—you can integrate your own rather than having to work with your provider's built-in offering. The NGINX controller must be exposed for external access. This is done using Service `type: LoadBalancer` on the NGINX controller service. On Kubernetes Engine, this creates a Google Cloud Network (TCP/IP) Load Balancer with NGINX controller Service as a backend. Google Cloud also creates the appropriate firewall rules within the Service's VPC to allow web HTTP(S) traffic to the load balancer frontend IP address.

#### NGINX Ingress Controller on Kubernetes Engine

The following flowchart is a visual representation of how an NGINX controller runs on a Kubernetes Engine cluster:

#### Deploy NGINX Ingress Controller

Now that you have the bigger picture in mind, let's go ahead and deploy the NGINX Ingress Controller. Run the following command to do so:

helm install –name nginx-ingress stable/nginx-ingress –set rbac.create=true

In the output under RESOURCES, you should see a similar output:

==> v1/Service

NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE

nginx-ingress-controller LoadBalancer 10.15.252.129

Note the second service, `nginx-ingress-default-backend`. The default backend is a Service which handles all URL paths and hosts the NGINX controller. The default backend exposes two URLs:

* `/healthz` that returns 200

* `/` that returns 404

Wait a few moments while the GCP L4 Load Balancer gets deployed. Confirm that the `nginx-ingress-controller` Service has been deployed and that you have an external IP address associated with the service by running the following command:

kubectl get service nginx-ingress-controller

You receive a similar output:

NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP

nginx-ingress-controller LoadBalancer 10.7.248.226 35.226.162.176

### Configure Ingress Resource to use NGINX Ingress Controller

An Ingress Resource object is a collection of L7 rules for routing inbound traffic to Kubernetes Services. Multiple rules can be defined in one Ingress Resource or they can be split up into multiple Ingress Resource manifests. The Ingress Resource also determines which controller to utilize to serve traffic. This can be set with an annotation, `kubernetes.io/ingress.class`, in the metadata section of the Ingress Resource. For the NGINX controller, you will use the nginx value as shown below:

annotations: kubernetes.io/ingress.class: nginx

On Kubernetes Engine, if no annotation is defined under the metadata section, the Ingress Resource uses the GCP GCLB L7 load balancer to serve traffic. This method can also be forced by setting the annotation's value to gce, like below:

annotations: kubernetes.io/ingress.class: gce

Let's create a simple Ingress Resource YAML file which uses the NGINX Ingress Controller and has one path rule defined by typing the following commands:

touch ingress-resource.yaml nano ingress-resource.yaml

Add the following content in `ingress-resource.yaml` file:

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1 kind: Ingress metadata: name: ingress-resource annotations: kubernetes.io/ingress.class: nginx nginx.ingress.kubernetes.io/ssl-redirect: “false” spec: rules:

- http:

paths:

- path: /hello backend: serviceName: hello-app servicePort: 8080 ```

then press Ctrl-X, then press Y, then press Enter to save the file.

The kind: Ingress dictates it is an Ingress Resource object. This Ingress Resource defines an inbound L7 rule for path /hello to service hello-app on port 8080.

Run the following command to apply those rules to our Kubernetes application:

kubectl apply -f ingress-resource.yaml

Verify that Ingress Resource has been created:

kubectl get ingress ingress-resource

Note: The IP address for the Ingress Resource will not be defined right away. Wait a few moments for the

ADDRESSfield to get populated.

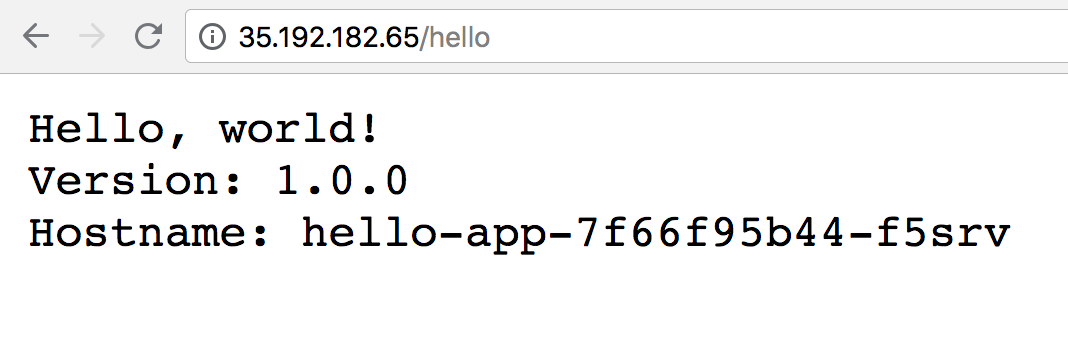

Test Ingress and default backend

You should now be able to access the web application by going to the EXTERNAL-IP/hello address of the NGINX ingress controller (found by running kubectl get service nginx-ingress-controller).

Open a new tab and go to the following, replacing the external-ip-of-ingress-controller with the external IP address of the NGINX ingress controller:

http://external-ip-of-ingress-controller/hello

Your page should look similar to the following:

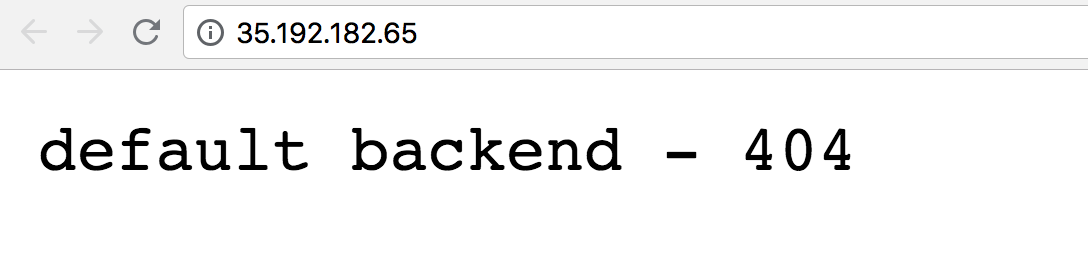

To check if the default-backend service is working properly, access any path (other than the path /hello defined in the Ingress Resource) and ensure you receive a 404 message. For example:

http://external-ip-of-ingress-controller/test

Your page should look similar to the following:

Distributed Load Testing Using Kubernetes

Overview

In this lab you will learn how to use Kubernetes Engine to deploy a distributed load testing framework. The framework uses multiple containers to create load testing traffic for a simple REST-based API. Although this solution tests a simple web application, the same pattern can be used to create more complex load testing scenarios such as gaming or Internet-of-Things (IoT) applications. This solution discusses the general architecture of a container-based load testing framework.

System under test

For this lab the system under test is a small web application deployed to Google App Engine. The application exposes basic REST-style endpoints to capture incoming HTTP POST requests (incoming data is not persisted).

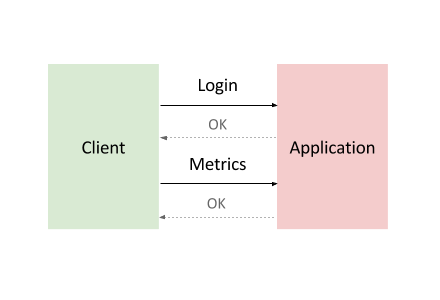

Example workloads

The application that you’ll deploy is modeled after the backend service component found in many Internet-of-Things (IoT) deployments. Devices first register with the service and then begin reporting metrics or sensor readings, while also periodically re-registering with the service.

Common backend service component interaction looks like this:

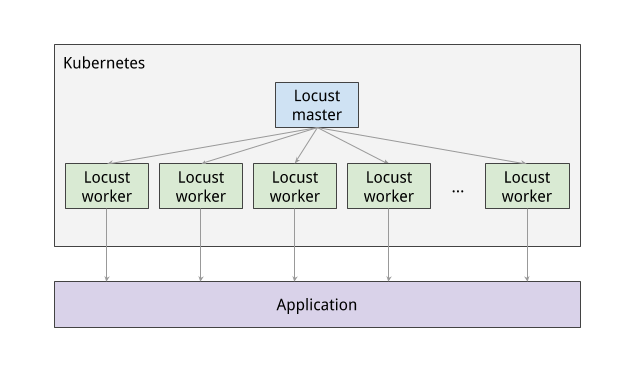

To model this interaction, you’ll use Locust, a distributed, Python-based load testing tool that is capable of distributing requests across multiple target paths. For example, Locust can distribute requests to the /login and /metrics target paths.

The workload is based on the interaction described above and is modeled as a set of Tasks in Locust. To approximate real-world clients, each Locust task is weighted. For example, registration happens once per thousand total client requests.

Container-based computing

-

The Locust container image is a Docker image that contains the Locust software.

-

A container cluster consists of at least one cluster master and multiple worker machines called nodes. These master and node machines run the Kubernetes cluster orchestration system. For more information about clusters, see the Kubernetes Engine documentation

-

A pod is one or more containers deployed together on one host, and the smallest compute unit that can be defined, deployed, and managed. Some pods contain only a single container. For example, in this lab, each of the Locust containers runs in its own pod.

-

A Deployment controller provides declarative updates for Pods and ReplicaSets. This lab has two deployments: one for locust-master and other for locust-worker.

-

Services

A particular pod can disappear for a variety of reasons, including node failure or intentional node disruption for updates or maintenance. This means that the IP address of a pod does not provide a reliable interface for that pod. A more reliable approach would use an abstract representation of that interface that never changes, even if the underlying pod disappears and is replaced by a new pod with a different IP address. A Kubernetes Engine service provides this type of abstract interface by defining a logical set of pods and a policy for accessing them.

In this lab there are several services that represent pods or sets of pods. For example, there is a service for the DNS server pod, another service for the Locust master pod, and a service that represents all 10 Locust worker pods.

The following diagram shows the contents of the master and worker nodes:

What you’ll do

- Create a system under test i.e. a small web application deployed to Google App Engine.

- Use Kubernetes Engine to deploy a distributed load testing framework.

- Create load testing traffic for a simple REST-based API.

Prerequisites

- Familiarity with App Engine and Kubernetes Engine GCP services.

- Familiarity with standard Linux text editors such as Vim, Emacs or Nano

Set project and zone

Define environment variables for the project id, region and zone you want to use for the lab.

PROJECT=$(gcloud config get-value project)

REGION=us-central1

ZONE=${REGION}-a

CLUSTER=gke-load-test

TARGET=${PROJECT}.appspot.com

gcloud config set compute/region $REGION

gcloud config set compute/zone $ZONE

Get the sample code and build a Docker image for the application

Get the source code from the repository by running:

git clone https://github.com/GoogleCloudPlatform/distributed-load-testing-using-kubernetes.git

Move into the directory:

cd distributed-load-testing-using-kubernetes/

Build docker image and store it in container registry.

gcloud builds submit --tag gcr.io/$PROJECT/locust-tasks:latest docker-image/.

Example Output:

ID CREATE_TIME DURATION SOURCE IMAGES STATUS

47f1b8f7-0b81-492c-aa3f-19b2b32e515d xxxxxxx 51S gs://project_id_cloudbuild/source/1554261539.12-a7945015d56748e796c55f17b448e368.tgz gcr.io/project_id/locust-tasks (+1 more) SUCCESS

Deploy Web Application

The sample-webapp folder contains a simple Google App Engine Python application as the “system under test”. To deploy the application to your project use the gcloud app deploy command:

gcloud app deploy sample-webapp/app.yaml

Note: You will need the URL of the deployed sample web application when deploying the

locust-masterandlocust-workerdeployments which is already stored inTARGETvariable.

Deploy Kubernetes Cluster

First create the Google Kubernetes Engine cluster using the gcloud command shown below:

gcloud container clusters create $CLUSTER \

--zone $ZONE \

--num-nodes=5

Example Output:

NAME LOCATION MASTER_VERSION MASTER_IP MACHINE_TYPE NODE_VERSION NUM_NODES STATUS

gke-load-test us-central1-a 1.11.7-gke.12 34.66.156.246 n1-standard-1 1.11.7-gke.12 5 RUNNING

Load testing master

The first component of the deployment is the Locust master, which is the entry point for executing the load testing tasks described above. The Locust master is deployed with a single replica because we need only one master.

The configuration for the master deployment specifies several elements, including the ports that need to be exposed by the container (8089 for web interface, 5557 and 5558 for communicating with workers). This information is later used to configure the Locust workers.

The following snippet contains the configuration for the ports:

ports:

- name: loc-master-web

containerPort: 8089

protocol: TCP

- name: loc-master-p1

containerPort: 5557

protocol: TCP

- name: loc-master-p2

containerPort: 5558

protocol: TCP

Deploy locust-master

Replace [TARGET_HOST] and [PROJECT_ID] in locust-master-controller.yaml and locust-worker-controller.yaml with the deployed endpoint and project-id respectively.

sed -i -e "s/\[TARGET_HOST\]/$TARGET/g" kubernetes-config/locust-master-controller.yaml

sed -i -e "s/\[TARGET_HOST\]/$TARGET/g" kubernetes-config/locust-worker-controller.yaml

sed -i -e "s/\[PROJECT_ID\]/$PROJECT/g" kubernetes-config/locust-master-controller.yaml

sed -i -e "s/\[PROJECT_ID\]/$PROJECT/g" kubernetes-config/locust-worker-controller.yaml

Deploy Locust master:

kubectl apply -f kubernetes-config/locust-master-controller.yaml

To confirm that the locust-master pod is created, run the following command:

kubectl get pods -l app=locust-master

Next, deploy the locust-master-service:

kubectl apply -f kubernetes-config/locust-master-service.yaml

This step will expose the pod with an internal DNS name (locust-master) and ports 8089, 5557, and 5558. As part of this step, the type: LoadBalancer directive in locust-master-service.yaml will tell Google Kubernetes Engine to create a Google Compute Engine forwarding-rule from a publicly avaialble IP address to the locust-master pod.

To view the newly created forwarding-rule, execute the following:

kubectl get svc locust-master

Example Output:

NAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE

locust-master LoadBalancer 10.59.244.88 35.222.161.198 8089:30865/TCP,5557:30707/TCP,5558:31327/TCP 1m

Load testing workers

The next component of the deployment includes the Locust workers, which execute the load testing tasks described above. The Locust workers are deployed by a single deployment that creates multiple pods. The pods are spread out across the Kubernetes cluster. Each pod uses environment variables to control important configuration information such as the hostname of the system under test and the hostname of the Locust master.

After the Locust workers are deployed, you can return to the Locust master web interface and see that the number of slaves corresponds to the number of deployed workers.

The following snippet contains the deployment configuration for the name, labels, and number of replicas:

apiVersion: "extensions/v1beta1"

kind: "Deployment"

metadata:

name: locust-worker

labels:

name: locust-worker

spec:

replicas: 5

selector:

matchLabels:

app: locust-worker

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: locust-worker

spec:

...

Deploy locust-worker

Now deploy locust-worker-controller:

kubectl apply -f kubernetes-config/locust-worker-controller.yaml

The locust-worker-controller is set to deploy 5 locust-worker pods. To confirm they were deployed run the following:

kubectl get pods -l app=locust-worker

Scaling up the number of simulated users will require an increase in the number of Locust worker pods. To increase the number of pods deployed by the deployment, Kubernetes offers the ability to resize deployments without redeploying them.

The following command scales the pool of Locust worker pods to 20:

kubectl scale deployment/locust-worker --replicas=20

o confirm that pods have launched and are ready, get the list of locust-worker pods:

kubectl get pods -l app=locust-worker

The following diagram shows the relationship between the Locust master and the Locust workers:

Execute Tests

To execute the Locust tests, get the external IP address by following command:

EXTERNAL_IP=$(kubectl get svc locust-master -o yaml | grep ip | awk -F": " '{print $NF}')

echo http://$EXTERNAL_IP:8089

Click the link and navigate to Locust master web interface.

Running Dedicated Game Servers in Google Kubernetes Engine

Packaging server applications as containers is quickly gaining traction across the tech landscape, and game companies are no exception. Many game companies are interested in using containers to improve VM utilization as well as take advantage of their isolated run-time paradigm. Despite high interest, many companies don’t know where to start.

This lab will show you how to use an expandable architecture for running a real-time, session-based multiplayer dedicated game server using Kubernetes on Google Kubernetes Engine. A scaling manager process is configured to automatically start and stop virtual machine instances as needed. Configuration of the machines as Kubernetes nodes is handled automatically by managed instance groups. The online game structure presented in this lab is intentionally simple, and places where additional complexity might be useful or necessary are pointed out where appropriate.

Objectives

- Create a container image of a popular open-source dedicated game server (DGS) on Linux using Docker. This container image adds only the binaries and necessary libraries to a base Linux image.

- Store the assets on a separate read-only persistent disk volume and mount them in the container at run-time.

- Setup and configure basic scheduler processes using the Kubernetes and Google Cloud APIs to spin up and down nodes to meet demand.

Before you begin start the download of the game client

In this lab you’ll be creating a game server, and to test the server, you need to connect to a game client. The OpenArena game client is available for many operating systems, as long as you can install it on your local machine. If you cannot install a game client on the machine you’re currently using, consider taking this lab when you are using a machine you can install a game client on. Validating your work by connecting to a game client is not required, you can choose not to. Taking this lab will still show you how to create a dedicated game server, you just won’t be able to confirm it works.

Install the OpenArena game client on your computer to test the connection to the game server at the end of the lab :

http://openarena.wikia.com/wiki/Manual/Install

This will take a while. Start working on the lab while it downloads, and check back in about 30 min to see if it’s finished. Then install the game client.

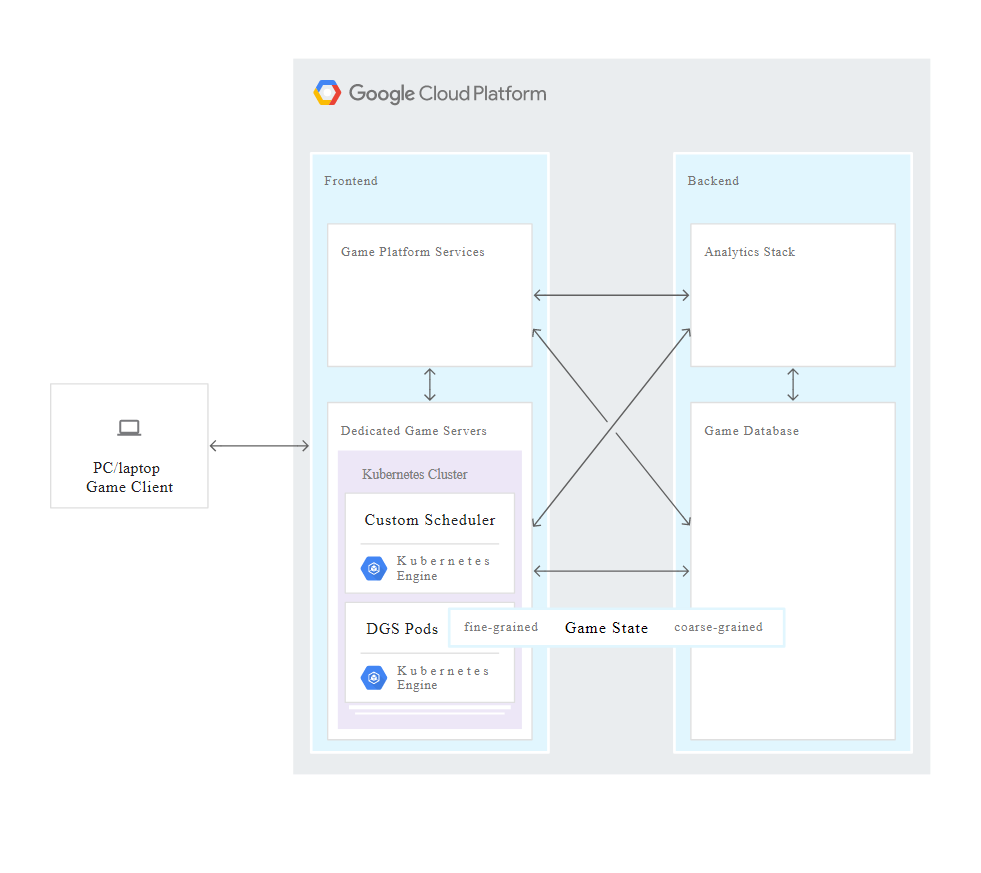

Architecture overview

The Overview of Cloud Game Infrastructure discusses the high-level components common to many online game architectures. In this lab you implement a Kubernetes DGS cluster frontend service and a scaling manager backend service. A full production game infrastructure would also include many other frontend and backend services which are outside the scope of this solution.

Constructive constraints

In an effort to produce an example that is both instructive and simple enough to extend, this lab assumes the following game constraints:

- This is a match-based real-time game with an authoritative DGS that simulates the game State.

- The DGS communicates over UDP.

- Each DGS process runs one match.

- All DGS processes generates approximately the same amount of load.

- Matches have a maximum length.

- DGS startup time is negligible, and ‘pre-warming’ of the dedicated game server process isn’t necessary.

- Customer experience impact should be avoided as much as possible:

- Once peak time has passed, matches should not be ended prematurely in order to scale down the number of VM instances.

- However, if the dedicated game server process encounters an issue and cannot continue, the match state is lost and the user is expected to join a new match.

- The DGS process loads static assets from disk but does not require write access to the assets.

- These constraints all have precedent within the game industry, and represent a real-world use case.

Note: Many of the commands in this lab require you to substitute your own values for those listed in the code. These substituted variables are capitalized and surrounded by angle brackets <>, such as

.

Containerizing the dedicated game server

In this lab, you’ll use OpenArena, a “community-produced deathmatch FPS based on GPL idTech3 technology”. Although this game’s technology is over fifteen years old, it’s still a good example of a common DGS pattern:

- A server binary is compiled from the same code base as the game client.

- The only data assets included in the server binary are those necessary for the server to run the simulation.

- The game server container image only adds the binaries and libraries necessary to run the server process to the base OS container image.

- Assets are mounted from a separate volume.

This architecture has many benefits: it speeds image distribution, reduces the update load as only binaries are replaced, and consumes less disk space.

Creating a dedicated game server binaries container image

For this lab, you cannot use Cloud Shell. You must install the GCP SDK in a client and prepare the environment so that you can create and work with docker images.

Create a VM instance to carry out lab tasks

In the Google Cloud Console Click Compute Engine > VM Instances.

Click Create Instance.

In the Identity and API access section select Allow full access to all Cloud APIs.

Click Create.

After your instance has deployed, click the SSH button. The remaining tasks for this lab will be carried out in the SSH console of this VM.

If the SSH console does not automatically open check the upper right of your browser window for a pop-up alert icon.

Click the pop-up alert icon, select Always allow pop-ups from https://console.cloud.google.com and then click Done.

Click the SSH button again to open the console.

Install kubectl and docker on your VM

Update the apt-get repositories in the VM:

sudo apt-get update

Install gcloud tools for Kubernetes:

sudo apt-get -y install kubectl

Install dependencies for docker:

sudo apt-get -y install \

apt-transport-https \

ca-certificates \

curl \

gnupg2 \

software-properties-common

Install Docker’s official GPG key:

curl -fsSL https://download.docker.com/linux/$(. /etc/os-release; echo "$ID")/gpg | sudo apt-key add -

Check that the GPG fingerprint of the Docker key you downloaded matches the expected value:

sudo apt-key fingerprint 0EBFCD88

You should see the following fingerprint in the output

pub 4096R/0EBFCD88 2017-02-22

Key fingerprint = 9DC8 5822 9FC7 DD38 854A E2D8 8D81 803C 0EBF CD88

uid Docker Release (CE deb) <docker@docker.com>

sub 4096R/F273FCD8 2017-02-22

Add the stable Docker repository:

sudo add-apt-repository "deb [arch=amd64] https://download.docker.com/linux/$(. /etc/os-release; echo "$ID") $(lsb_release -cs) stable"

Update the apt-get repositories:

sudo apt-get update

Install Docker-ce:

sudo apt-get -y install docker-ce

Configure Docker to run as a non-root user:

sudo usermod -aG docker $USER

Exit from the SSH session then reconnect by clicking the SSH button for your VM instance.

You have to disconnect and reconnect the SSH session because the group permission change does not take effect until the user logs in again.

Confirm that you can run Docker as a non-root user:

docker run hello-world

You should see the following message in the output.

Hello from Docker!

This message shows that your installation appears to be working correctly.

Download the Sample Game Server Demo

Clone the demo example:

git clone https://github.com/GoogleCloudPlatform/gke-dedicated-game-server.git

Creating a dedicated game server binaries container image

Prepare the working environment Select the gcr.io region nearest to your Kubernetes Engine cluster (for example, us for the United States, eu for Europe, or asia for Asia, as noted in the documentation).

Substitute your <PROJECT_ID> and your gcr.io region for <GCR_REGION> in this command:

export GCR_REGION=<REGION> PROJECT_ID=<PROJECT_ID>

printf "$GCR_REGION \n$PROJECT_ID\n"

The updated command will look something like:

export GCR_REGION=us PROJECT_ID=qwiklabs-gcp-6bcf12ce01eb3dc7

printf "$GCR_REGION \n$PROJECT_ID\n"

Generate a new container image

You first create a Dockerfile describing the image to be built. This lab’s Debian-based Dockerfile is in the repository at openarena/Dockerfile.

cd gke-dedicated-game-server/openarena

Run this Docker build command to generate the container image and tag it. For ease of use with Google Kubernetes Engine, we’re using Google Container Registry ( gcr.io ).

docker build -t \

${GCR_REGION}.gcr.io/${PROJECT_ID}/openarena:0.8.8 .

You may see some warnings and errors during the build but if the command completes with two statements starting with Successfully built and Successfully tagged then you can proceed.

Upload the container image to an image repository:

gcloud docker -- push \

${GCR_REGION}.gcr.io/${PROJECT_ID}/openarena:0.8.8

Generate an assets disk